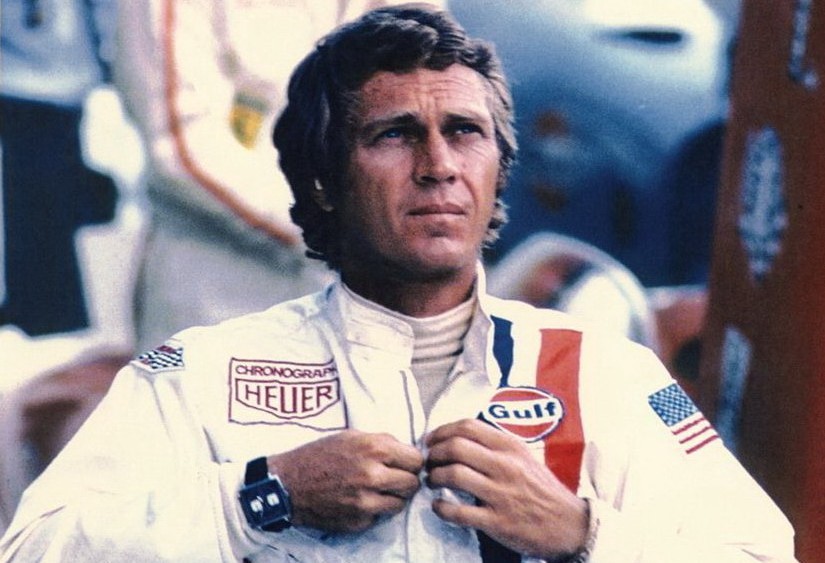

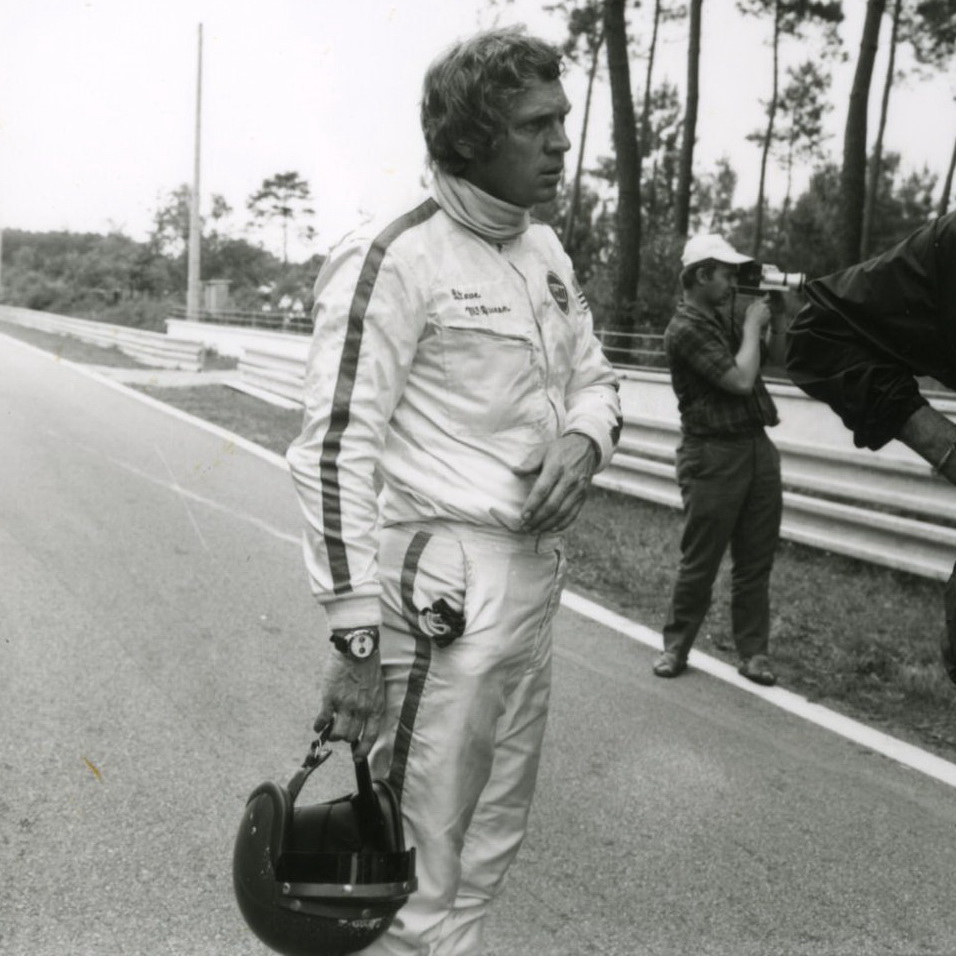

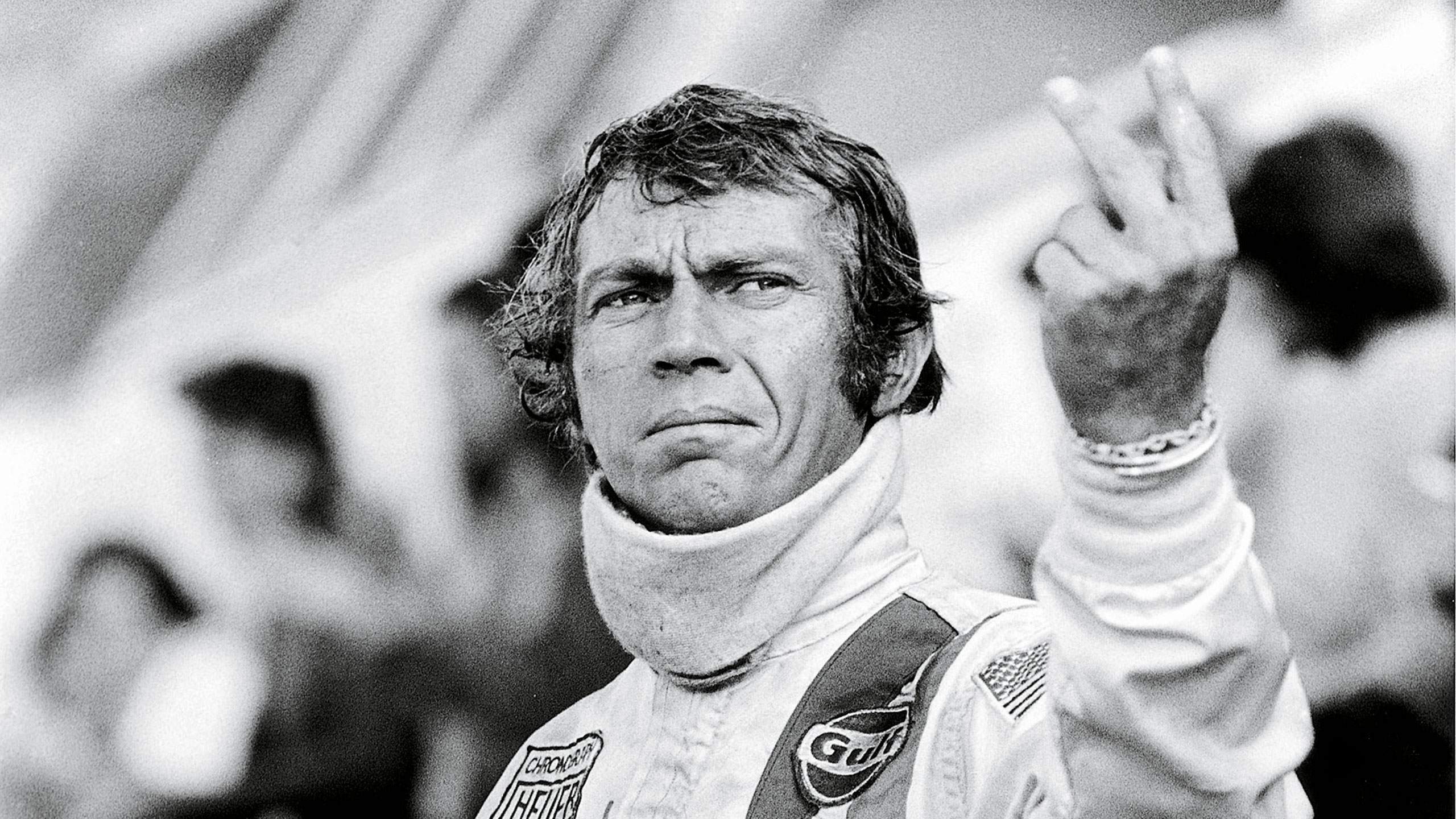

There are few associations between a hero and his watch that have the enduring strength of the connection between Steve McQueen and his Heuer Monaco, worn in the film Le Mans. Introduced in 1969 and worn by McQueen in 1970, the “McQueen Monaco” has been re-issued in numerous configurations over the last 20 years. Pick up a magazine or visit a mall, and we see the images of the “King of Cool”, his Porsche 917, and his racing suit and racing watch.

Beyond the world of watches, the imagery of Steve McQueen is celebrated among those who study film and social and cultural history. The market for McQueen memorabilia jumps from one level to the next, so that cars driven by McQueen, and items that he wore, are at the top of the Hollywood hierarchy.

Much is known about the Heuer Monaco worn by McQueen, but for every point of information that has been settled, it seems that we face new questions. How did McQueen come to wear the Heuer Monaco? Was it selected by McQueen or the property master of Le Mans? How many Monacos were used at Le Mans and for what purposes – during filming, for stills, etc. Who brought them to Le Mans and where did they end up after the filming? Who owned them – Steve McQueen himself, his production company or the property master? And what about the ones that ended up on the wrists of “friends of Steve”? With the sale of one of McQueen’s Monacos for $799,500 in July 2012, theses questions became more urgent.

Michael Clerizo, who writes about watches for the Wall Street Journal, was determined to unravel the mysteries of McQueen’s Monacos, and has published his findings today in the Watches and Jewelry supplement to the WSJ — “The Hunt for McQueen’s Monacos“. [PDF is HERE] Through his unwavering determination over the course of months of research, Clerizo has solved many of these mysteries.

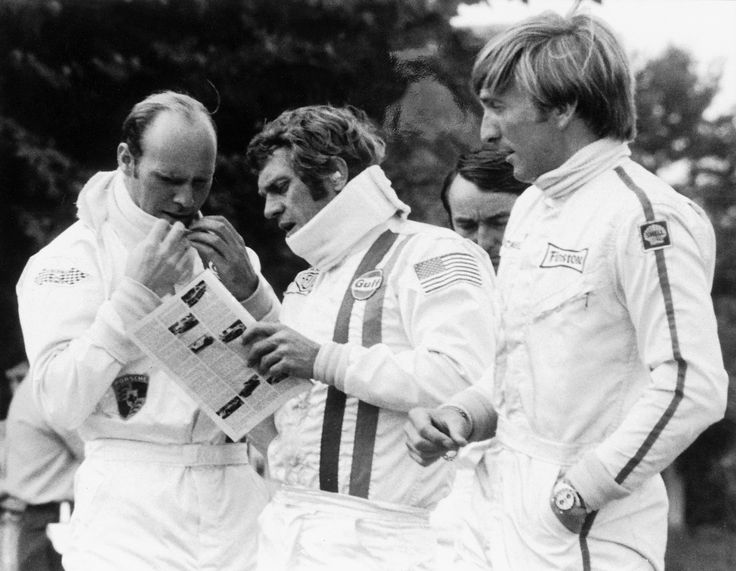

Whether investigating watches or more important things, historians cherish “primary sources”. Eye witness accounts, photos and film, newspaper reports and original documents provide the most reliable information as we seek to solve the puzzles of history. Forty six years after the filming of Le Mans, however, the ranks of the eye witnesses are thinning and, in some instances, their memories may be fading. There are abundant film and photo resources covering the making of Le Mans, but we sometimes have the sense that we have already seen all that there is to see. In some instances, interpreting what we are seeing can be difficult. We see various racers wearing different watches on different days, but have no good explanation.

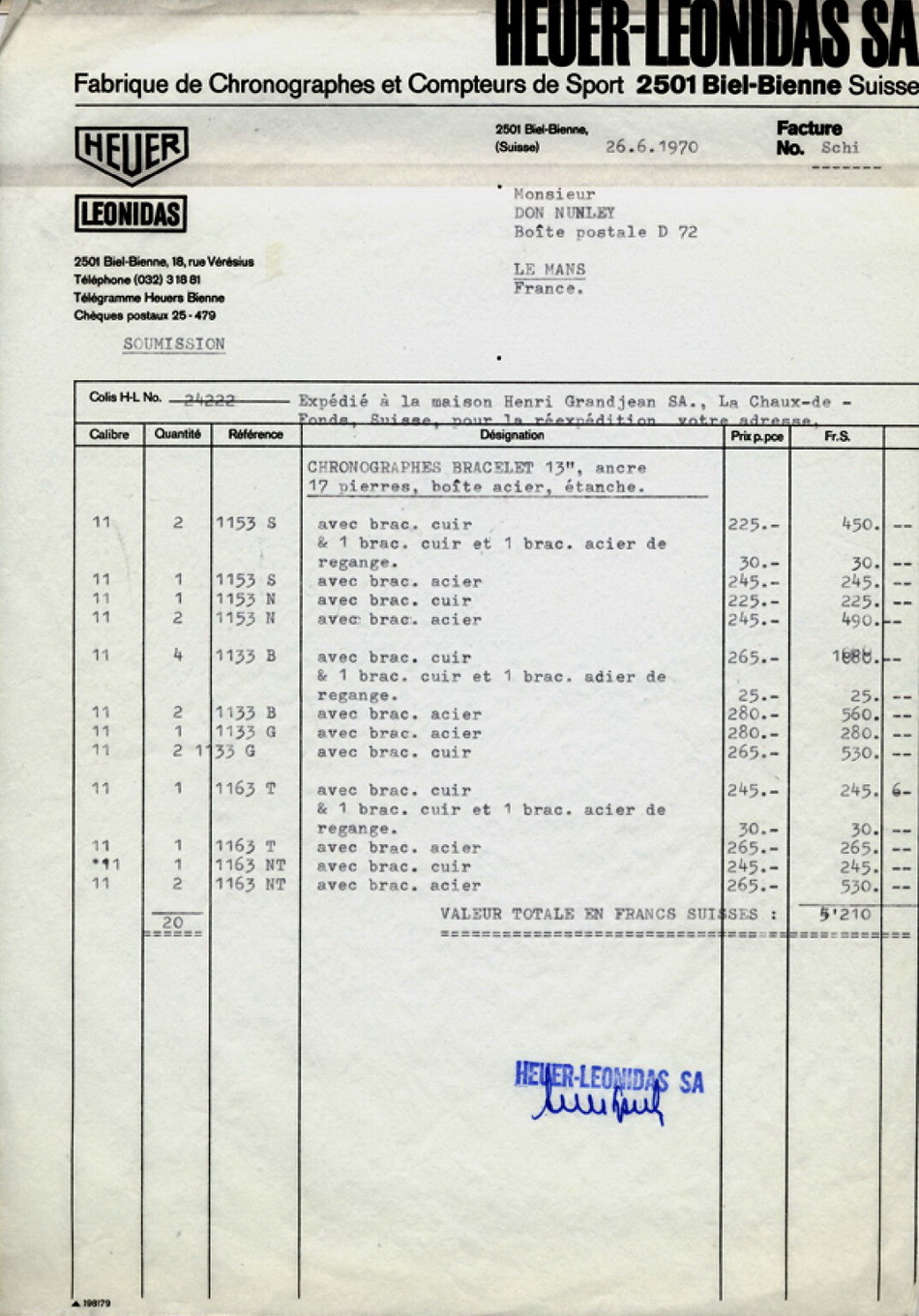

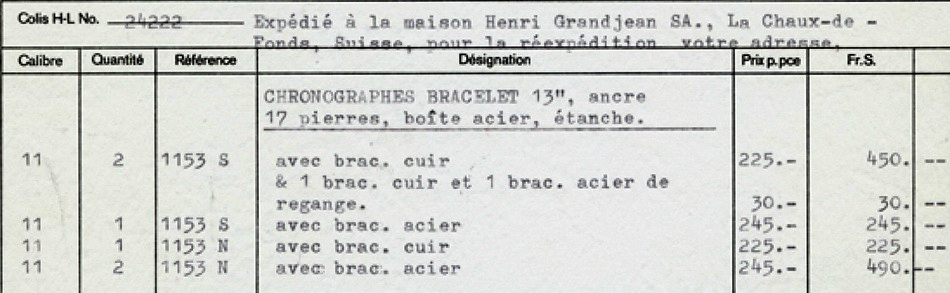

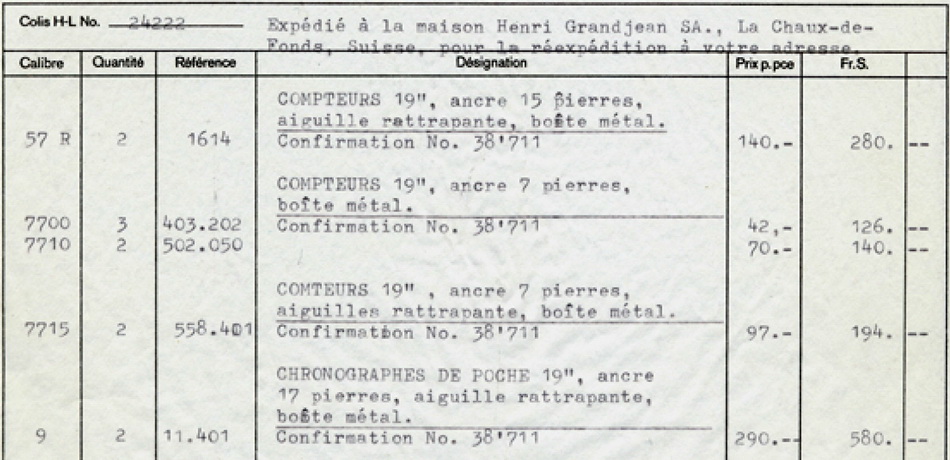

So the community that collects these vintage chronographs celebrates when a researcher uncovers a new source of information. Among the primary sources that Clerizo uncovered in researching his article, the document that was most important to his detective work was the invoice, dated June 26, 1970, from Heuer Leonidas (in Switzerland) to Don Nunley (the property master of Le Mans), covering the Heuer timepieces that were shipped to Le Mans. This invoice covers 26 chronographs, a handful of stopwatches and other timers, and some related accessories.

Among the chronographs listed on the invoice, we find the six samples of the midnight blue Heuer Monaco (Reference 1133B) that were destined to become the “McQueen Monaco”. In this posting, we will explore this invoice in detail, to understand the Heuer timepieces that were “present at the creation” of the much-celebrated relationship between Steve McQueen and his Heuer Monaco.

The Invoice

Before examining the line entries on the invoice, we should the transaction that was being documented. With an invoice date of June 26, 1970, Heuer-Leonidas (in Biel-Bienne, Switzerland) was selling 26 chronographs, six stopwatches, and various accessories to Don Nunley, the property master of the film Le Mans. Nunley was then in Le Mans, France, where the filming had begun, just a few days earlier (June 22, 1970). The timepieces were to be shipped to Nunley by Henri Grandjean, SA, a company in La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland. As we describe below, the timepieces were divided into two groups, with some to remain the property of Don Nunley and others to be returned to Heuer-Leonidas.

Although they bear the same Invoice No. – the rather odd-looking “Schi” — it is useful to note that there were actually two separate invoices that covered the Heuer timepieces shipped to Le Mans.

The invoice shown below is a single page and lists 20 chronographs that Heuer Leonidas shipped to Le Mans – six Carreras, nine Monacos, and five Autavias.

We notice that after listing the watches, we see a Total Value (valuer totale) of 5,210 Swiss Francs. We will refer to this invoice, that lists these 20 chronographs, as the “Primary Invoice”.

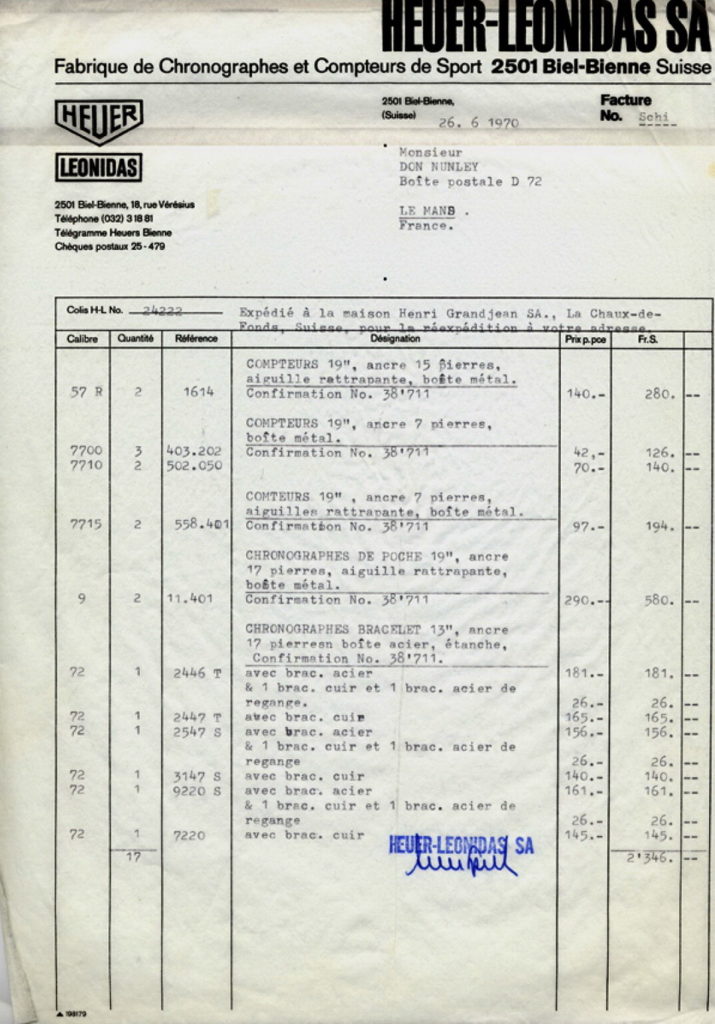

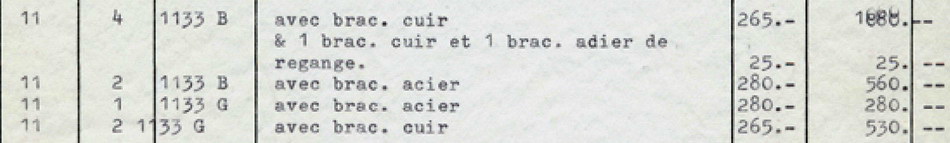

In addition to this Primary Invoice, however, Heuer Leonidas issued a second invoice to Don Nunley (which we will call the “Second Invoice”). This second invoice bears the same date and Invoice No. (Schi), and includes six chronographs, 11 stopwatches and pocket chronographs, and some additional accessories.

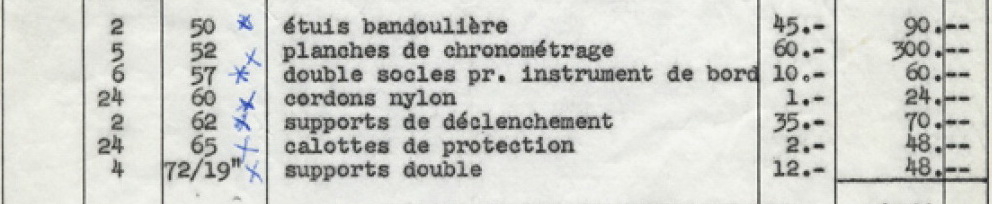

This second invoice is comprised of two pages, with the first page listing 17 timepieces (with a total value of 2,346 Swiss Francs), and the second page adding two additional timepieces 67 various accessories (timing boards, neck cords, stopwatch holders, etc. With the sub-total of 2,346 Swiss Francs of timepieces carried forward from the first page, this Second Invoice has a total value of 3,336 Swiss Francs.

Next, we will work through these invoices, line-by-line, to identify the watches that were shipped to Le Mans.

The Primary Invoice

Automatic Carreras

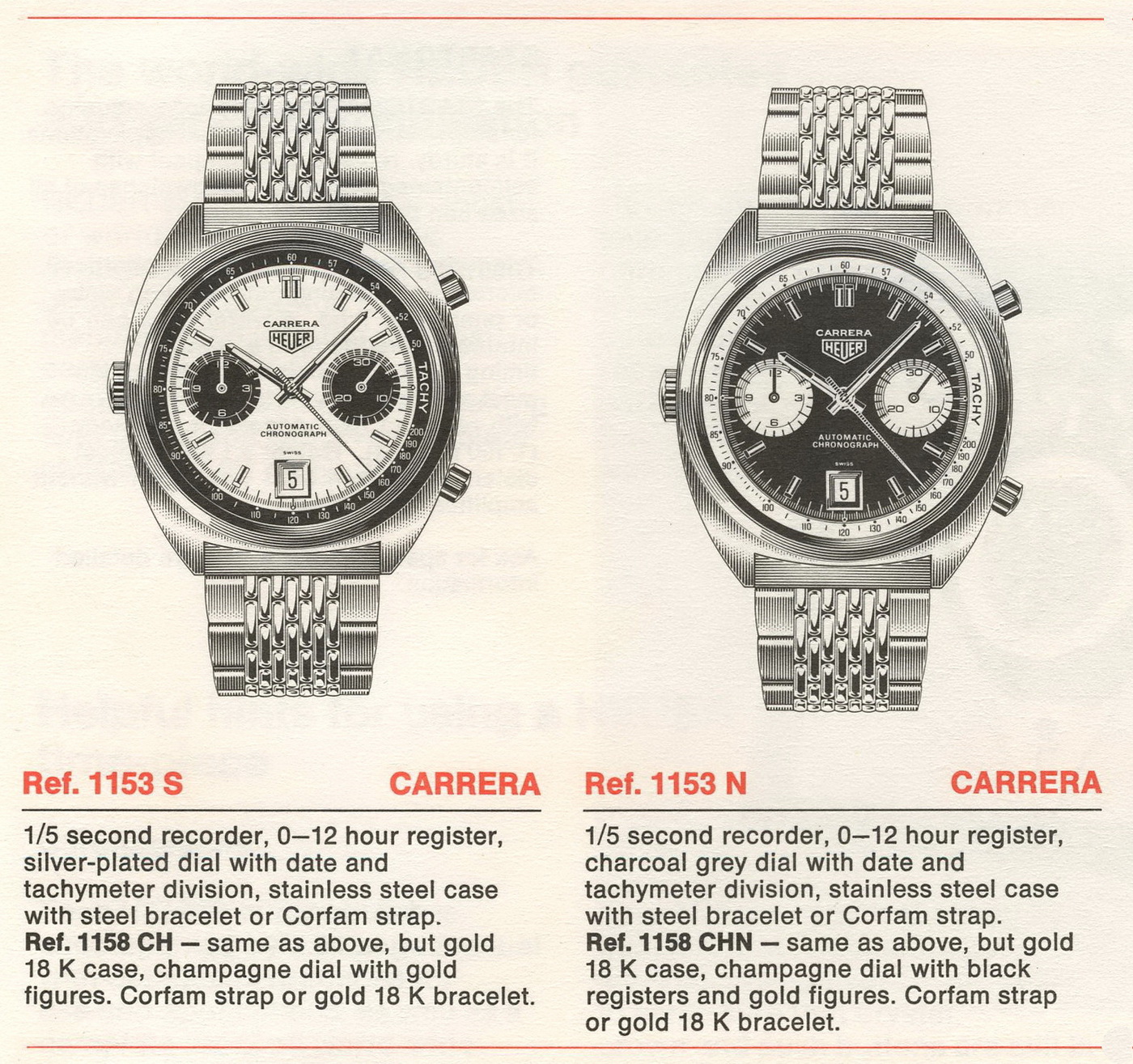

The first group of chronographs listed on the primary invoice consists of six automatic Carreras, Reference 1153.

The first three listed are Reference 1153 S, indicating that they have a silver dial with black recorders. Two of these are on leather straps (or actually a synthetic leather known as “Corfam”) and one is on a stainless steel bracelet (brac. acier). We see that Mr. Nunley also ordered some extra bands – one leather strap and one stainless steel bracelet. The last three automatic Carreras are Reference 1153 N, meaning that they have a charcoal gray dial and white registers.

Automatic Autavias

The third group of chronographs shown on the Primary Invoice consists of five automatic Autavias, Reference 1163.

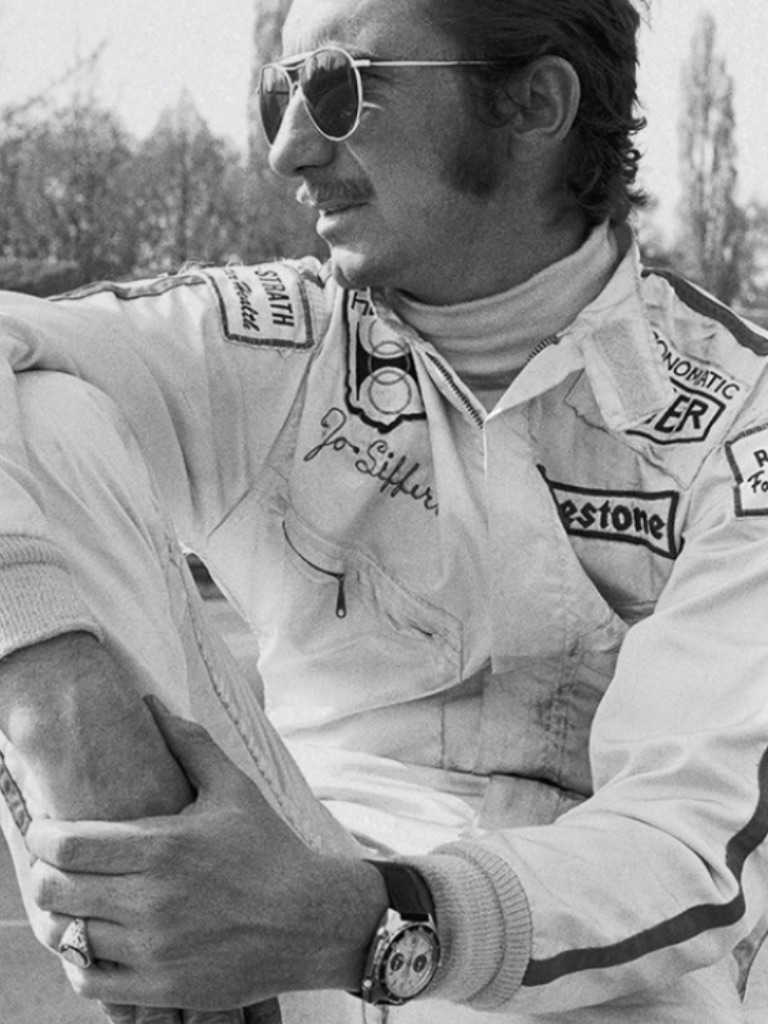

Two of these are Reference 1163 T, meaning that they have a white dial and black registers along with a Tachymeter bezel. This was the model of chronograph worn by Steve McQueen’s racing mentor, Jo Siffert, and it is known to collectors as the “Siffert Autavia”.

The last three chronographs shown on this Primary Invoice are a bit of a puzzle — Reference 1163 NT Autavias. The “N” tells us that these Autavias had a black dial (and white registers), and the “T” indicates that the bezel was marked with a Tachymeter scale, rather than the Minutes and Hours markings that were the standard for the black-dialed Reference 1163 Autavias. (Yes, this invoice may prove, once and for all, that when a good customer preferred a particular bezel, Heuer was satisfy the customer’s request.)

Along with these five Autavias, Mr. Nunley ordered two extra bands – one Corfam strap and one stainless steel bracelet.

Automatic Monacos

Now, we get to the “Stars of the Show” . . . literally.

The middle section of the Primary Invoice lists nine automatic Monaco chronographs, Reference 1153. The first two entries of this section are Reference 1133B Monacos, indicating that they have midnight blue dials and white recorders. These were the Monaco chronographs that Steve McQueen wore for the filming of Le Mans; these were the ones that would soon and forever be known as the “McQueen Monacos”. Four of the six were on Corfam straps and two of them were on stainless steel bracelets.

In addition to these six blue Monacos, the this invoice includes three gray Monacos, Reference 1133G. Once again, we see that Mr. Nunley ordered two extra bands – one Corfam strap and one stainless steel bracelet.

The Second Invoice

The Second Invoice includes six chronographs, 11 stopwatches and pocket chronographs, and some additional accessories, described on two pages. Once again, we will work through the invoice, line-by-line.

Eleven Stopwatches and Timers

The first section of the Second Invoice shows an order for 11 stopwatches and timers, comprised of five different references.

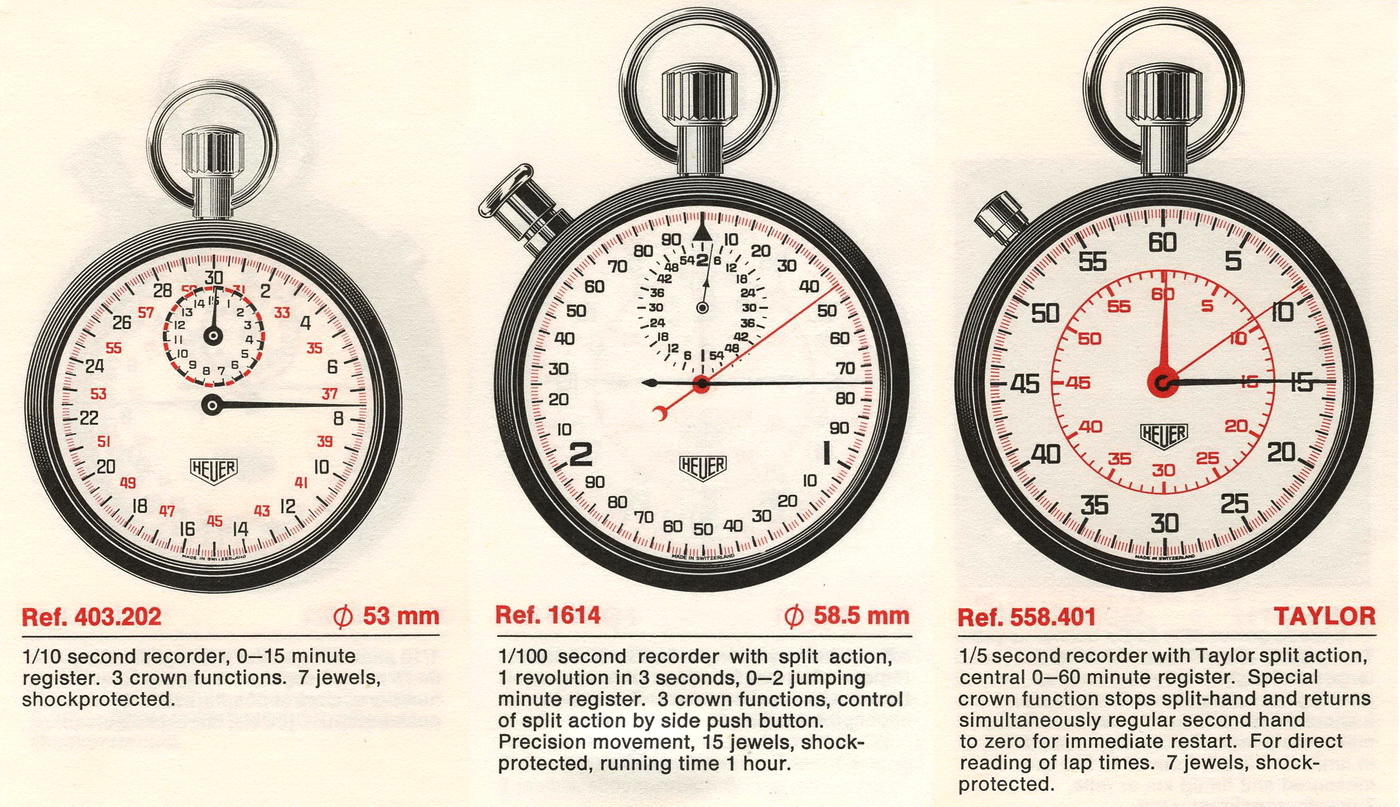

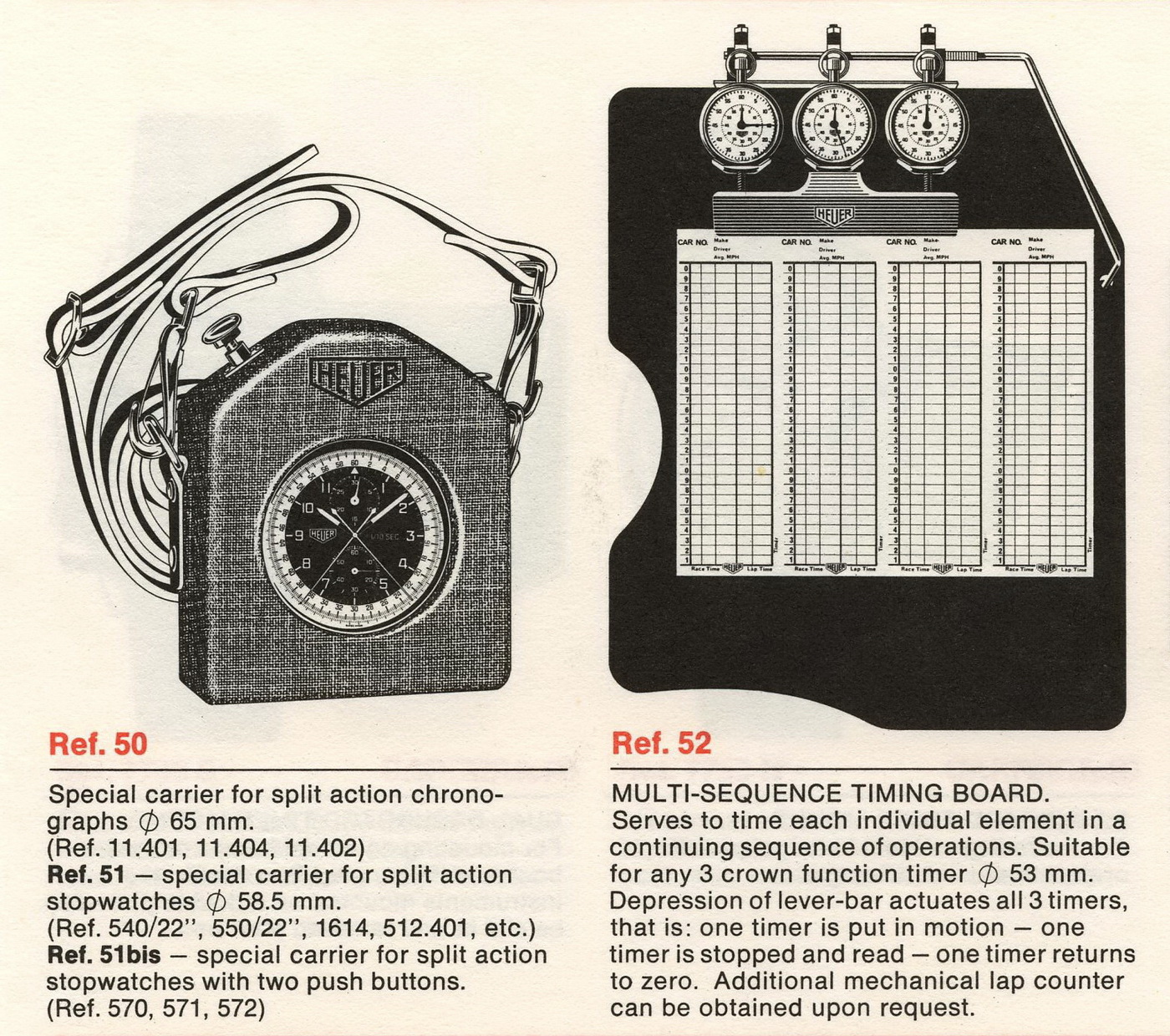

Three of the References are handheld stopwatches – Reference 1614, Reference 403.202, and Reference 558.401. The catalog scan (below) provides detailed descriptions of each of these three references.

The stopwatch on the left is the simplest (and least expensive) of the group, having a 15 minute capacity and a single three-function crown (for start, stop and reset). The two larger stopwatches on the right have a split second feature, meaning that one hand can be stopped, then continue running, so that the user can time the differential between two cars. The Reference 1614 stopwatch is the most sophisticated of this group, timing to 1/100 of a second, with a capacity of 2 minutes. The Reference 558.401 offers 1/5 second timing, with a capacity of 60 minutes. This stopwatch uses the “Taylor” system of split second timing.

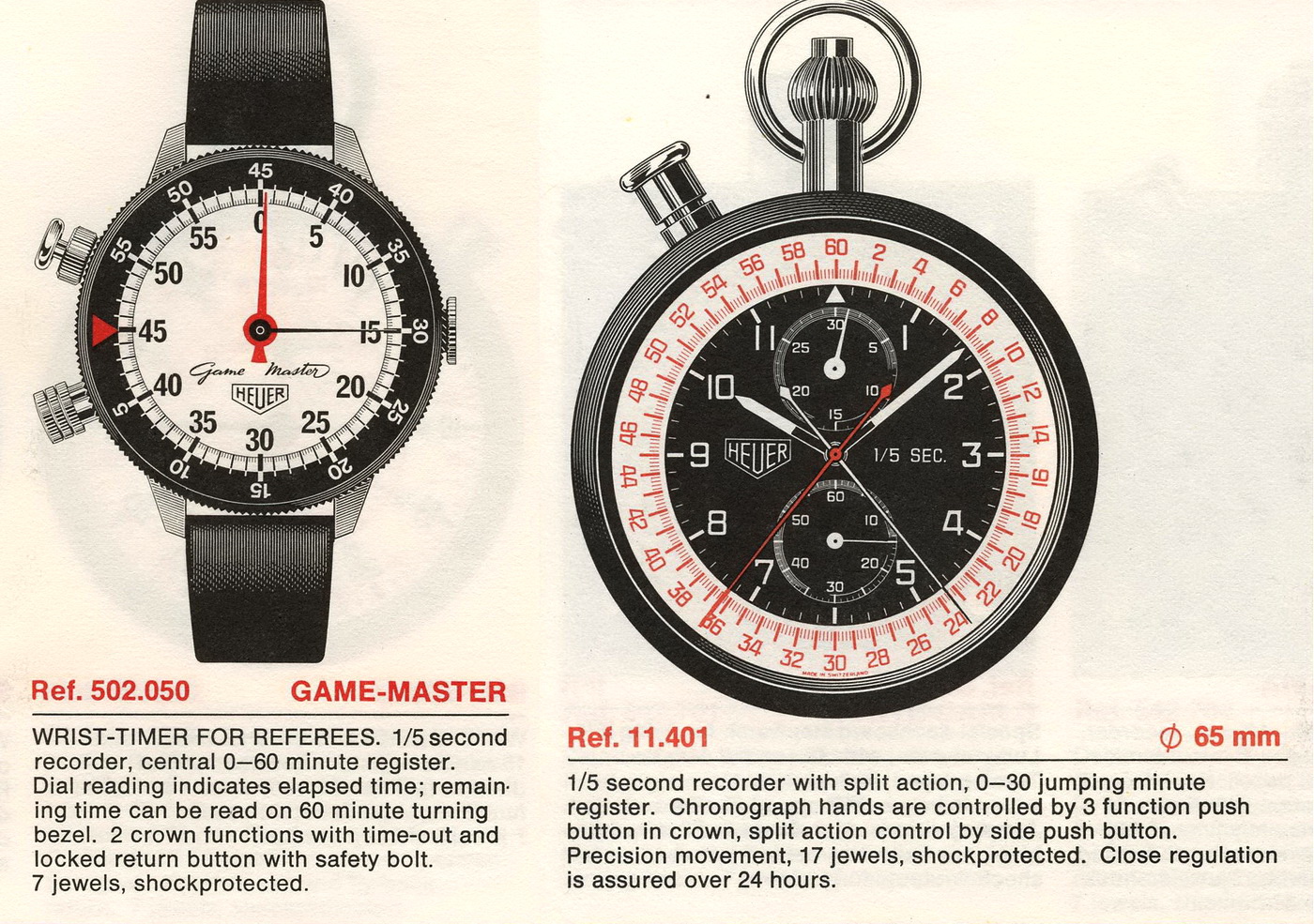

Showing that Mr. Nunley wanted a nice variety of timers, this section of the invoice includes two unusual types of timepieces – the Game-Master (Reference 502.050) and a split second Pocket Chronograph (Reference 11.401).

The Game-Master is described as a “wrist-timer for referees”, the traditional style lugs and leather strap allowing the stopwatch to be worn as a wristwatch. The rotating inner bezel is marked for “countdown”, and the stopwatch provides time-in / time-out operation. The Reference 11.401 pocket chronograph is a full chronograph, showing the time of day (with running seconds at six o’clock), while also offering a split second stopwatch, with 30 minute capacity. This pocket chronograph is the most expensive item that Mr Nunley ordered – at 290 CHF, costing 10 Francs more than the Monaco chronograph – and is also the largest, at 65 millimeters.

Six Manual-Wind Chronographs

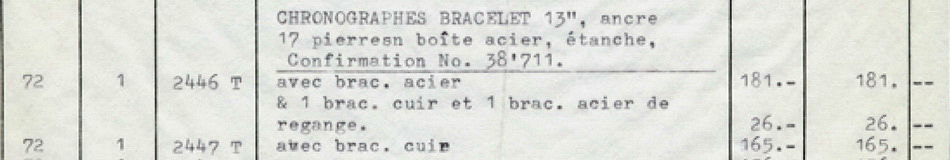

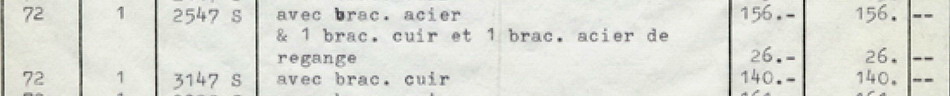

The Primary Invoice included 20 automatic chronographs, and the next section of the Second Invoice covers six manual-winding chronographs.

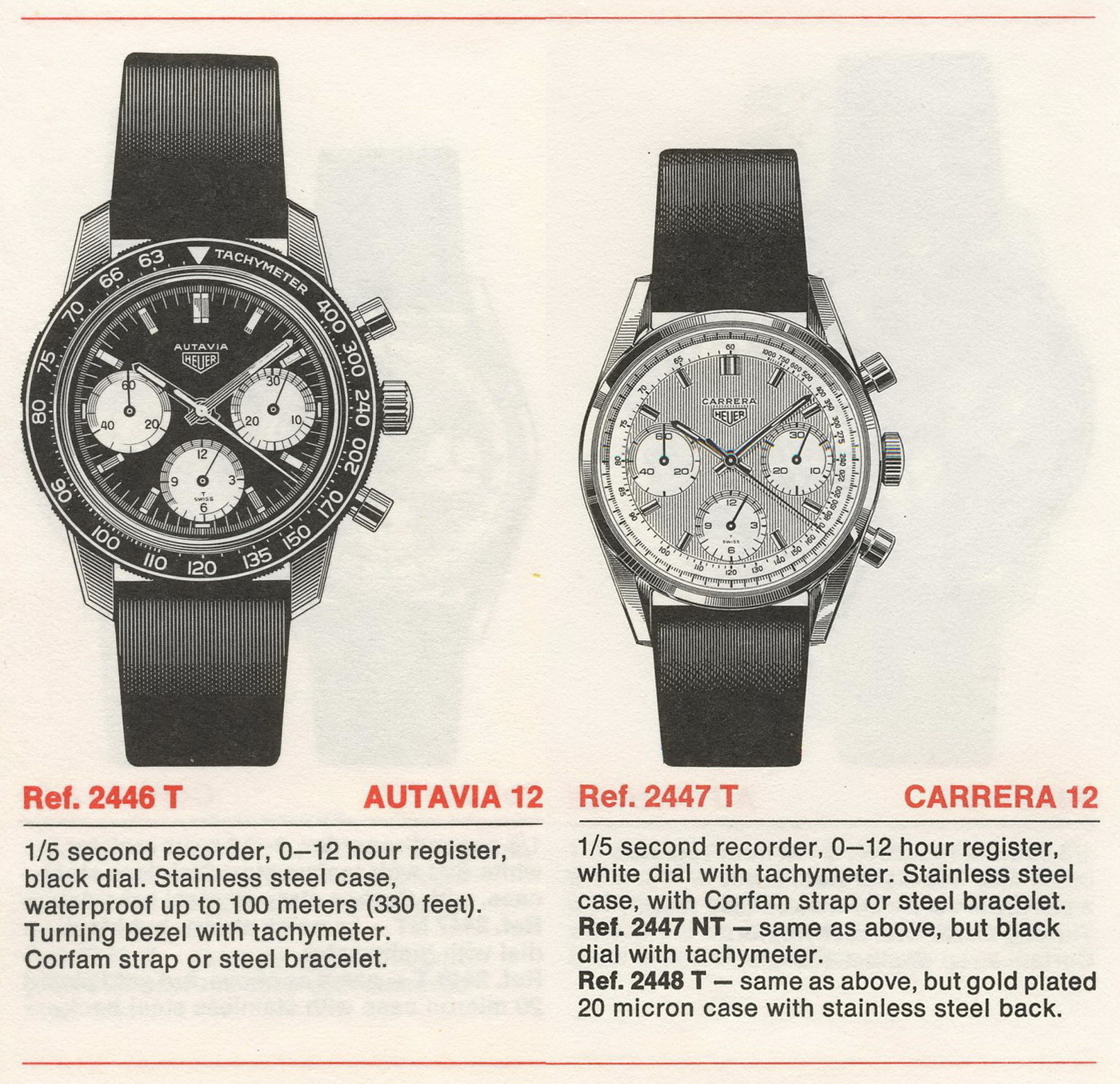

First up are two chronographs powered by Valjoux 72 movements, the Reference 2446 T (which is an Autavia) and the Reference 2447 T (which is a Carrera).

In keeping with the racing mood that Mr. Nunley hope to evoke through these timepieces, both these chronographs were the versions with Tachymeter indications. The Autavia is Reference 2446 T, and in 1970, this would have been the version in the new “Compressor” case.

Based on the 1970/71 Heuer catalog, the Carrera Reference 2447 T would have been the Carrera 12, with a white dial and the Tachymeter scale printed on the dial.

The next two entries on the invoice are two chronographs that we might not have expected to see at Le Mans, given the trend toward the large automatic Autavia, Carrera and Monaco chronographs that had been introduced in 1969. These are two of the Carrera “Dato” chronographs, both with silver dials.

The Reference 2547 S is the Carrera 12 Dato, a three register chronograph, with a triple calendar (indicating day, date and month). The Reference 3147 S is the Carrera 45 Dato, a one-register chronograph, with a 45-minute recorder at three o’clock and the date window at nine o’clock.

The final entries in this section of the Second Invoice describe more chronographs that we might not have expected to see at Le Mans — two Camaro chronographs.

The Reference 9220 S is a two-register Camaro, powered by the Valjoux 92 movement, and the Reference 7220 S is a three-register model, powered by the Valjoux 72. Like the two Carrera Datos, these two Camaros offer a very different look than the big automatic chronographs, a look that we may not instantly associate with Steve McQueen and the culture of racing.

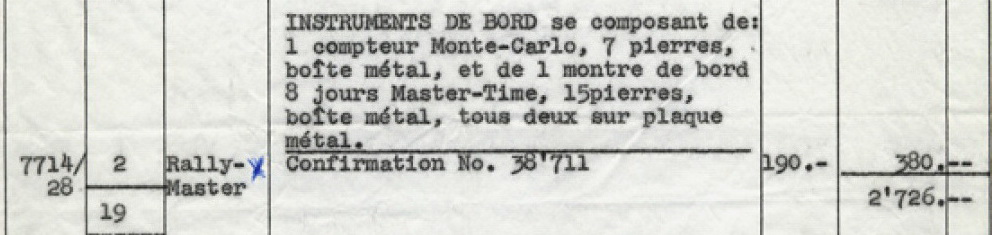

Rally-Master Pair

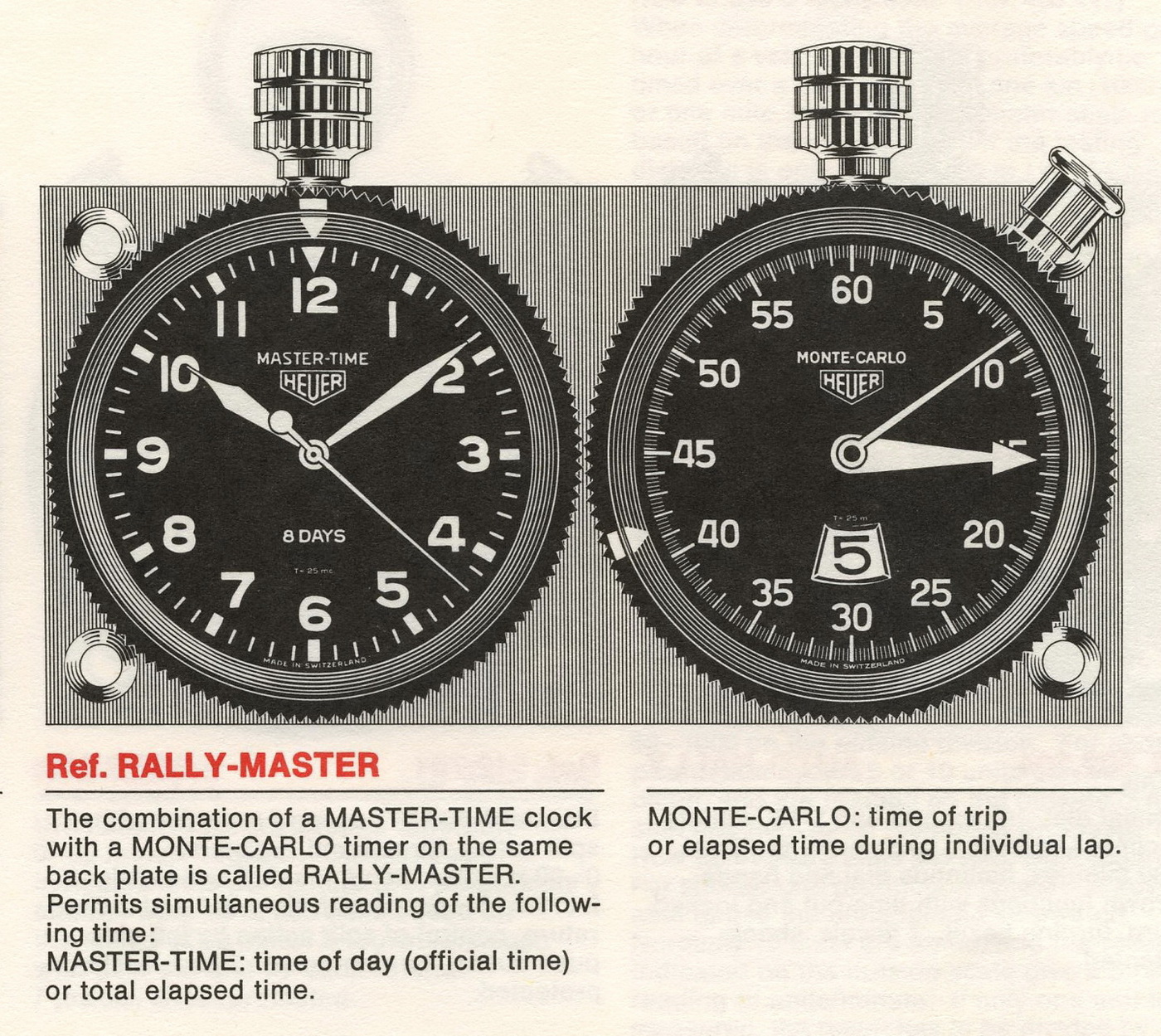

One of the keys to Heuer’s prominence in the world of motorsports was its production of dashbaord timers. Beginning with the launch of the Autavia dashboard timer in 1933, Heuer offered a variety of clocks, stopwatches and even full chronographs that were mounted to the dashboards of rally cars. It’s not surprising then that Mr. Nunley ordered a Rally-Master pair, as part of his equipment for the filming of Le Mans.

While rally drivers and navigators could specify their favorite combinations of timers, to be mounted on back-plates with one, two, three or four positions, the pair described on the invoice was the classic “Rally-Master” pair — the Master Time 8-day clock on the left and the Monte Carlo 12-hour stopwatch on the right.

The Accessories

A good property master seeks to use physical items to create a look on the screen, and the property master also must be prepared for any situation that may arise during filming. For the filming of Le Mans, Don Nunley ordered a broad variety of boards, holders and cases that would be used with the Heuer timers. The invoice includes an interesting array of accessories, some of which were specifically related to the stopwatches that Nunley had ordered and others that would have been used with other timers.

Examining each of these items, we begin with a carrier designed to hold the pocket chronograph (Reference TBD), as Nunley had included on the invoice. The Multi-Sequence Timing Board was a favorite of 1960s racing teams, and throughout 1950s, 60s and 70s, Heuer offered them in a variety of configurations. The fact that Nunley ordered five of the timing boards, but only a single 53 millimeter stopwatch, suggests either that there would be another order of timing equipment or that there were timepieces already on hand.

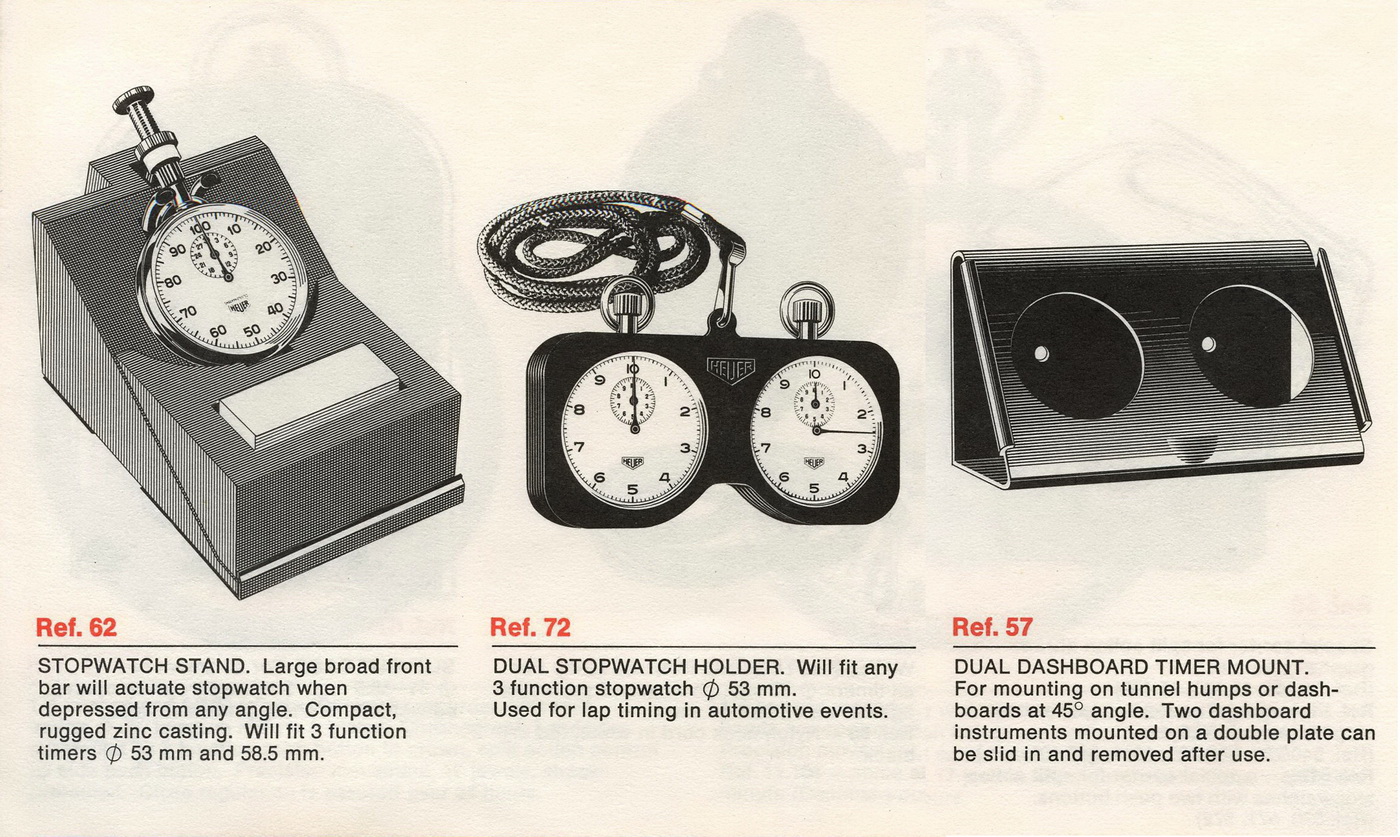

The last items on Mr. Nunley’s invoice were protective holders for stopwatches. The one on the left is a simple Rubber Cap that protects the stopwatch and improves the handling of the stopwatch. Nunley ordered 24 of these Rubber Caps, in the larger 58 millimeter size, along with 24 nylon neck cords for these rubber caps.

Finally, we see some additional devices for holding stopwatches and timers. The Stopwatch Stand (on the left) is attached to a bench or table, and allows the user to operate the stopwatch with one hand. The Dual Stopwatch Holder (center) allows the user to wear a pair of stopwatches on a lanyard. The Dual Dashboard Timer Mount is used to attach a pair of timers to a dashboard, also allowing them to be easily removed from the car.

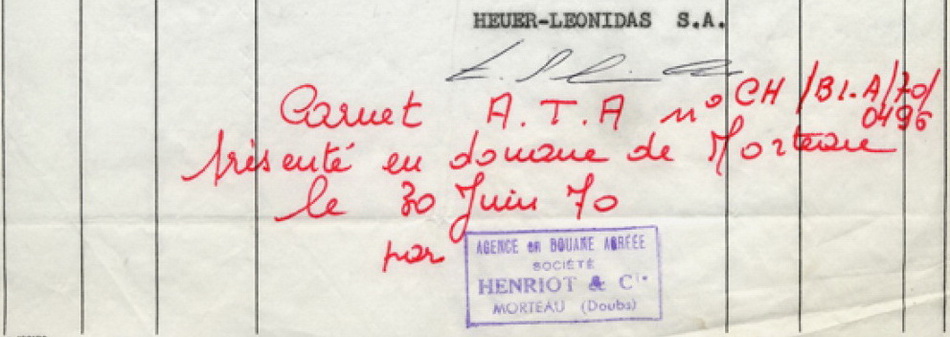

The Carnet

At the bottom of the second page of the Second Invoice, we see some handwriting (in bright red ink) that is critical to our understanding of the Heuers used at Le Mans. A Carnet ATA is an international customs and temporary export-import document, for the temporary import of items that will be returned (re-exported) within a one year period. So long as the goods are re-exported within the allotted time frame, no duties or taxes are due. The acronym “ATA” is a combination of French and English terms “Admission Temporaire/Temporary Admission.”

For those who collect the vintage Heuers, the presence of the Carnet ATA indicates that Heuer-Leonidas provided all the items on the Second Invoice to Don Nunley, under customs regulations that required the items to be returned to the company within one year. Assuming that Nunley complied with this undertaking to return the items, the Carnat ATA would explain why we have heard no claims of Carrera 12 Datos, Autavia Reference 2446 or Camaros tracing their provenance to the filming of Le Mans.

And Why Does This Matter?

Forty six years after the filming of Le Mans, there will never be certainty regarding the Heuer timepieces that were used in the filming (and those that were not). There were a lot of racecar drivers (earning $150 per day for their work), crews working on the cars and on the film, and a large entourage that seemed to be milling around the track. The invoice that we have examined describes one shipment of Heuer timepieces, but there must have been other deliveries of watches and plenty on hand, with the racers and their crews. Still, Michael Clerizo has interviewed just about everyone in the “chain of title” of McQueen’s Monacos, and validated the provenance of six of them. Beyond the six McQueen Monacos, the invoice establishes that many other Heuer timepieces were used at Le Mans, including some models that had never been part of the discussion – manual winding Carreras and Autavias, for example.

If Don Nunley and Jack Heuer were seeking to cover the “silver screen” with Heuer timepieces, they were successful. And this is as it should be, because in the 1960s and 1970s, the racers – whether McQueen and Siffert or weekend sports car club racers — wore Heuer chronographs, and the crews used Heuer stopwatches. Scan this posting, and you have a depiction of 39 Heuer timepieces shipped to the filming of Le Mans, including the ones worn by Steve McQueen. Yes, he was the King of Cool. He emulated his racing heroes, and for the past 46 years, watch enthusiasts have emulated McQueen.

Special Thanks

Sincere thanks to Michael Clerizo, for involving me in this fascinating research project. We have been talking about these six Monacos for the past 15 weeks, and I am happy to report that the vertigo usually associated with the topic has subsided. Thanks to Hans Schrag for helping me understand certain aspects of the invoice, as he has helped me understand the world of Heuers, circa 1970. Finally, thanks to Michael Eisenberg, for helping me track these watches over the years; I’m very happy that one of them is in your collection.

Additional Reading

The following are recommended for those interested in Steve McQueen and Le Mans:

- In the Driving Seat with Steve McQueen, The Telegraph, November 7, 2015

- Earlier OnTheDash postings covering the “Worn by McQueen” Monacos — HERE and HERE

- OnTheDash posting about the sale of McQueen’s racing suit (for $800,000)

Jeff Stein

November 17, 2016