In a posting just prior to Baselworld 2013, we pondered the question of what the new Carrera Caliber 36 chronographs would look like. We had some excellent clues, from the “Teaser” image posted by TAG Heuer in the run-up to Basel, and were able to make some good guesses about the appearance and features of these new chronographs.

Now that TAG Heuer has introduced the the Carrera Calibre 36 at Basel, and released photographs and specifications, we can provide an introduction to these chronographs. We will begin with a description of the watches, and then explore some Heuer history, to understand the origins of these watches and place them in the context of Heuer’s heritage.

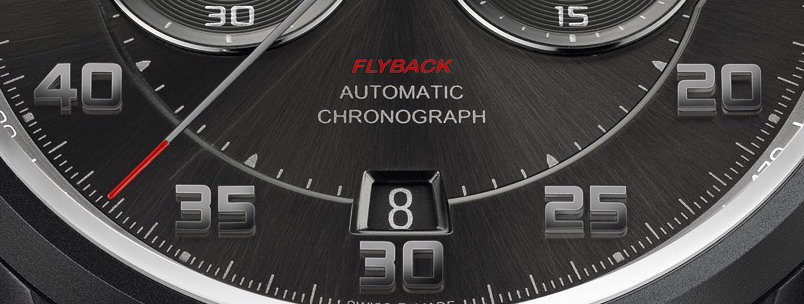

Three Versions of the Carrera Calibre 36 “Flyback” Chronograph

TAG Heuer has introduced three versions of the Carrera Calibre 36 “Flyback” chronograph, as follows:

- an anthracite dial with a black outer track, in a stainless steel case (above, left),

- an anthracite dial with a silver outer track, in a stainless steel case (above, center) and

- a “racing” model with an anthracite dial and black outer track, in a titanium case (above, right).

All three chronographs are powered by TAG Heuer’s Calibre 36 movement, being Tag Heuer’s version of the legendary “El Primero” movement, which was developed and is still used by Zenith, another brand in the LVMH family. The new Carrera Calibre 36 chronographs add an interesting complication, in that all have the “flyback” feature (which we will explain later).

The Carrera Calibre 36 Flyback chronographs measure 43 millimeters, with a sapphire crystals, front and back. They are water resistant to 100 meters.

The Carrera Calibre 36 Flyback Chronographs

The new Carrera Calibre 36 Flyback models feature “stopwatch inspired” dials. The center area of the dial (in anthracite on both models) is dedicated to the normal “time of day” function, while the outer track of the dial — with the 5-10-15-20 numerals — is used for reading the chronograph second hand. This explains the different lengths of the hands — relatively short hands are used to read the “time of day” (in the inner track), while the chronograph second hand is longer, to read seconds on the outer track. The red tip of the chronograph second hand emphasizes that this hand is read on the outer track.

“Racing” Model, with Titanium Case

Every product launch or international watch fair seems to have a “Wow Watch”, and the “Racing” version of the Carrera Calibre 36 Flyback seems to win that title for the Carreras introduced at Basel. The movement and functions are identical to those of the stainless steel models, but the case is sandblasted grade 2 titanium, with a coating of black titanium carbide. The Arabic numerals and the hands are “black gold”. A flange between the dial and the crystal is marked with a tachymeter scale, with the 60, 80, 120 and 240 in red.

The Dial — Stopwatch Inspired

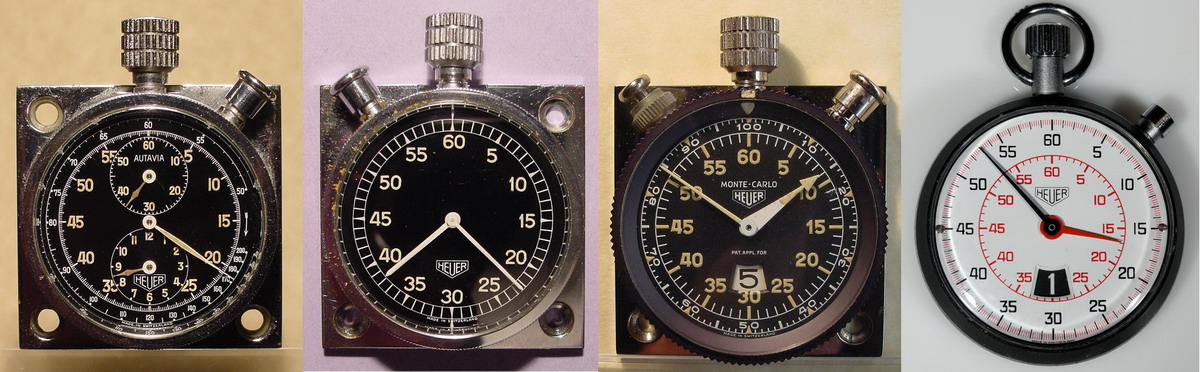

The dial design of the Carrera Calibre 36 may have had its origins in the mid-1950s, when Jack Heuer and his teammate lost the Swiss rally championship because Jack Heuer misread the minute counter on his dash-mounted Autavia timer (sample shown below, on the left). At that moment, Jack Heuer decided that the legibility of the dashboard timers could be improved by moving the minute hand to the center pinion, so that the driver or navigator does not squint to see the small recorder on the Autavia. Following this approach, Heuer soon introduced the Auto Rallye timer (shown second, below), which featured center-mounted minute and second hands. Next came the legendary Monte Carlo dashboard timer, in 1959, which kept the minute hand on the center pinion and added the disc to indicate the hours.

Redesigning the dashboard timers to improve legibility was a relatively simple task, as there were only three models in the catalog — Monte Carlo (12-hour timer); Sebring (split-second timer); and Auto-Rallye (60-minute timer). (The Master Time clock and Super Autavia dashboard chronograph were not part of the make-over.) In 1960, to mark the 100th anniversary of the company, Heuer undertook a larger task — re-designing its line of stopwatches to improve their legibility.

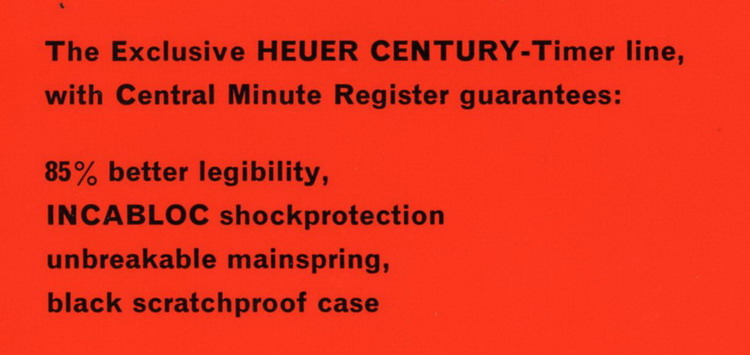

The key feature of the re-designed Century stopwatches was a “dual track” or “double scale” arrangement for the dial. Just as Heuer had relocated the minute recorder of the dashboard Autavia, so that the minute hand could be center-mounted, the Century line of stopwatches used this same approach. Instead of the small minute recorders, usually located at the top of the dial, Heuer used the center area of the dial for the minute track, with the minutes marked in red, as shown on the four “Century” models, shown in the center below.

A comparison of the “before” and “after” design of Heuer’s basic 12-hour stopwatches (below) illustrates the improved legibility of the new Century design. Both these stopwatches indicate 1 hour, 16 minutes and 53 seconds, but the Century design offers much greater legibility, especially in reading the minutes. According to Heuer catalogs of the period, the new design offered 83 percent improved legibility.

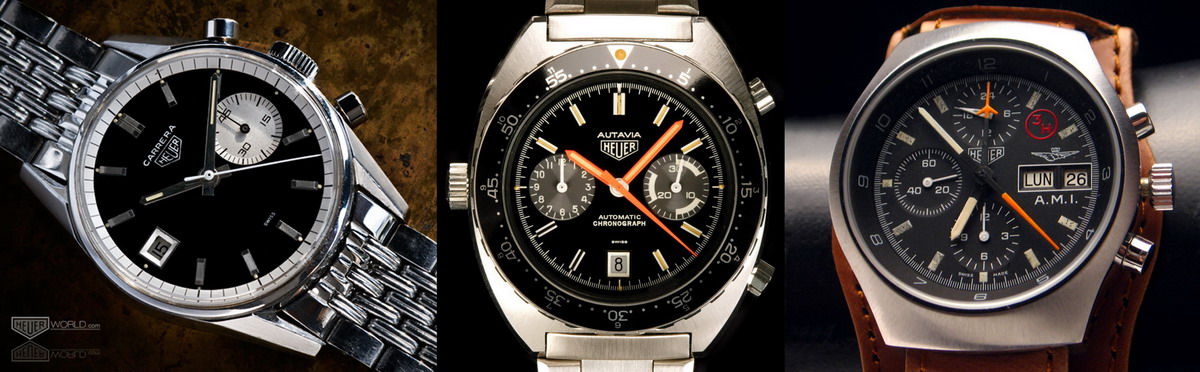

While the Carreras of the 1960s did not employ the “dual track” design of the Century stopwatches, the design of the first Carreras was driven by the same criteria that drove the re-design of Heuer’s stopwatches — legibility and simplicity. Racers had come to rely on Heuer stopwatches, and the Carrera would capture the same qualities in a wrist chronograph.

TAG Heuer has used “stopwatch inspired” designs for several of its recent models. For example, we see the “double scale” arrangement on the Carrera Mikrograph and Miktotimer Flying 1000, both introduced in 2011. In view of the importance of stopwatches in establishing Heuer as a leading brand for racers and motorsports enthusiasts in the 1960s, it is entirely fitting for TAG Heuer to draw on this style and imagery for its current line of racing chronographs.

So What’s a “Flyback”?

Having considered the design of the Carrera Calibre 36 dial, we can focus on the word that appears in red on the dial of this new chronograph — “Flyback”.

The “flyback” function is relatively simple to explain. While the chronograph is running, you take a reading (i.e., you note that 1 minute, 36 seconds have elapsed), and you push a pusher one time to instantly restart the chronograph (at zero), while the chronograph continues to run. Accordingly, at the instant that the chronograph “flies back” to zero, it begins timing the second interval. (The French term for flyback is helpful, with “retour en vol” meaning to “return on flight”.) With a traditional chronograph, the user would need three pushes to accomplish this task – using the top pusher to stop the chronograph, the bottom pusher to reset the chronograph, and the top pusher to restart the chronograph. Because three separate steps are required, there will be some loss of accuracy, in the timing of the new interval; there is also the possibility that the user will get the sequence wrong, so that the timing will not be accomplished.

The usual example of flyback timing is the pilot in a holding pattern The pilot must fly in a straight line for a certain amount of time (say, one minute), execute a 180 degree turn, and then fly in the opposite direction for a certain amount of time (say, one minute and 15 seconds, if he is going into a headwind), and then execute another 180 degree turn. The flyback allows the pilot to complete the timing of one interval, while instantly starting the timing of the next interval, with no time lag between the timing of these intervals.

A doctor timing a patient’s pulse rate provides another example of the usefulness of a flyback chronograph. Say, for example, that a doctor wants to see how a patient’s pulse rate may be changing over a short period of time. Using the Longines flyback chronograph (shown below), he starts the chronograph; counts 30 pulsations; and notes the pulse rate on the outer scale. He hits the flyback pusher, and is instantly timing the next 30 pulsations, with no gap or lag between the two events he is timing.

While flyback chronographs are useful for pilots, doctors and racers, they also prove to be useful for everyday life. The runner may want to capture her splits, reading the time for “Mile One”, just as she starts “Mile Two”. The sprinter wants to time his 400 meter sprints, as he allows himself no more than 60 second of rest between each sprint. While inexpensive digital watches may allow such interval timing, the flyback feature enables the mechanical chronograph to perform the same function.

Flyback versus Split Seconds?

There is sometimes confusion between the flyback and split seconds functions. As described above, “flyback” allows the chronograph to instantly reset to zero, and restart, all with a single push. “Split second” timing is entirely different, with the key elements being that the chronograph has two second hands, which are “split” to mark two different intervals.

With the chronograph running, a pusher is used to stop the split second hand, so that the user sees that a car passes a point at the 2 minute, 42 second mark (in the stopwatch shown below right); the next car comes by at the 2 minute, 48 second mark, so the user sees that there is a 6 second interval between the cars. A second push of the split second pusher returns the split second hand to the main second hand, and they continue running together, until the next measurement is taken.

“Split second” is referred to as “rattrapante” in French (meaning to “catch up”) and “doppelchrono” in German (meaning a double chronograph).

Split second timing is very important in auto racing and rallying, for example, to determine the differential between two racers or between a target time of a rally segment and the actual elapsed time. Heuer held a dominant position as the split second pocket chronograph of choice for rally teams and organizers, with the split second pocket chronographs in leather carrying cases being the standard equipment used at checkpoints.

Despite Heuer’s association with split second timing — in stopwatches, pocket chronographs and dashboard timers — neither Heuer nor TAG Heuer has ever produced a split second wrist chronograph.

The Legendary Flyback Chronographs

The “flyback” complication is well-established in the history of chronographs, usually being associated with flying. Breitling may have introduced the flyback function in the 1920s, but Longines obtained the first patent on the flyback in the mid-1930s, with its 13ZN movement, and Longines is closely associated with flyback chronographs.

German pilots chronographs from the 1930s through the 1950s often had the flyback feature, for example, models produced by Glashutte and Hanhart.

In the 1950s, the French air force issued a specification for its pilots chronographs, including features such as the flyback function and a rotating bezel, with this specification referred to as the “Type XX”. The most famous of the Type XX flyback chronographs was made by Breguet, although Dodane and Auricoste also produced Type XX chronographs.

The Breguet Type XX is regarded as the ultimate flyback chronograph for pilots, being introduced in 1954 and sold to the air forces of several countries. (Showing the depth of the Breguet-aviation connection, the Breguet Type XIX was not a watch, but an airplane, being the first airplane to fly non-stop from Paris to New York (taking 37 hours for the trip, in 1930).

This Hodinkee posting covers the history of the Breguet Type XX chronograph, and ABlogToWatch presents this interesting look at a collection of Breguet Type XX chronographs.

Heuer’s Tradition in Flyback Chronographs.

Leonidas had introduced a distinctive pilots chronograph in the early 1960s, which was issued by the German Air Force (Bundeswehr) to its pilots. With Heuer’s acquisition of Leonidas in 1964, Heuer acquired this chronograph, and the “Bund” would soon be recognized as one of the iconic Heuers. Bund chronographs used three different movements — Valjoux 23; Valjoux 222 and Valjoux 230 – and all of them provided the flyback feature. Heuer produced the Bund chronograph throughout the 1960s, also being issued by the air forces of other countries.

. . . and in Pilots Chronographs

While Heuer’s heritage in flyback chronographs may be limited to a single model, Heuer enjoys a rich heritage of producing chronographs for both military and civilian pilots. From the Reference 348 issued to German pilots in the 1930s, to Lemania powered chronograph issued to Italian Air Force pilots in the mid-1980s, the legibility and reliability of Heuer chronographs made them perfect for air force pilots. In the 1960s and 70s, we saw Heuer chronographs issued by the air forces of Argentina, Belgian Congo, Israel, Italy, Kenya and Sweden.

Just as Heuer focused on selling stopwatches and chronographs to racers and motorsports enthusiasts in the 1960s and 1970s, Heuer marketed a broad line of chronographs, panel-mounted timers and stopwatches to civilian pilots throughout the world.

In two historic uses of Heuer stopwatches by the ultimate pilots, in 1962, John Glenn strapped a stopwatch to his spacesuit for America’s first orbital flight, and seven years later, NASA officials at Mission Control, in Houston, used a Heuer stopwatch to time the landing of “The Eagle” on the lunar surface. (The models used by John Glenn and for the lunar landing are shown below.)

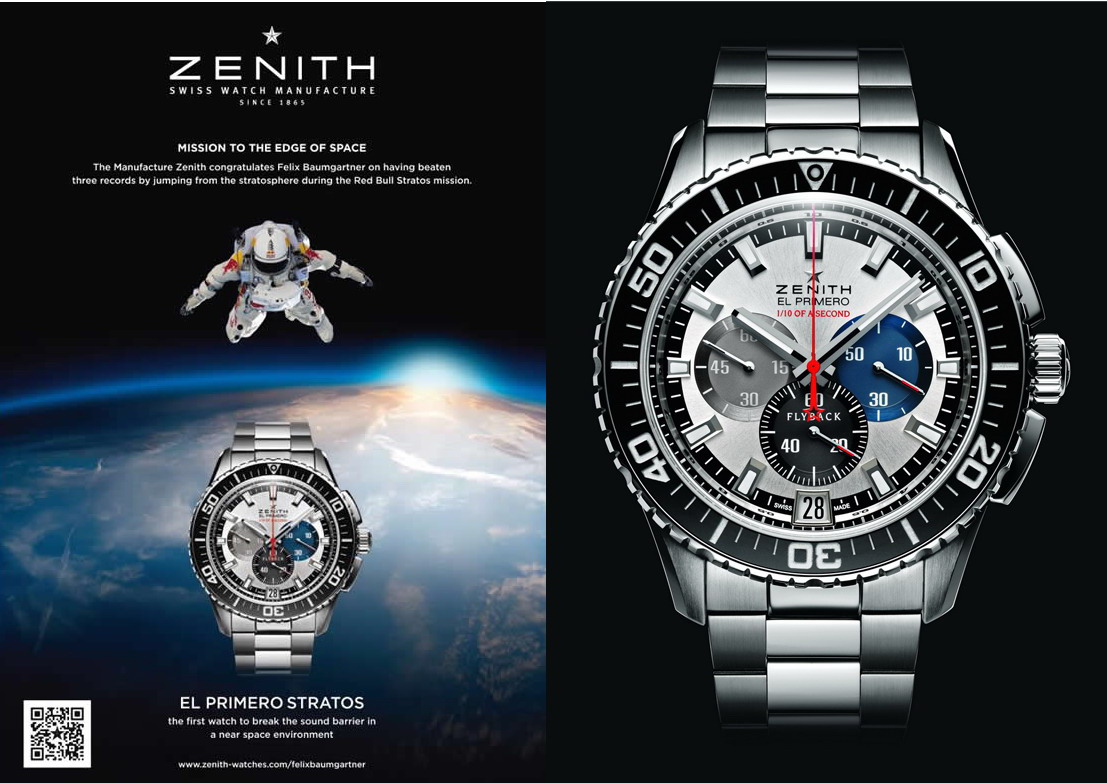

The Zenith El Primero Flybacks

Zenith introduced the El Primero movement in 1969, as the first automatic chronograph with an integrated movement. The El Primero is a high-beat movement, operating at 36,600 vibrations per hour (for 1/10 second indication), with a classic tri-compax arrangement, plus a date (in the 4:30 position). The El Primero movement is well respected among enthusiasts, for the beauty of its integrated design, for its place in horological history and for the superb chronographs that it has powered. [Have a look at our “El Primero Cheat Sheet” to see some of these legendary chronographs.]

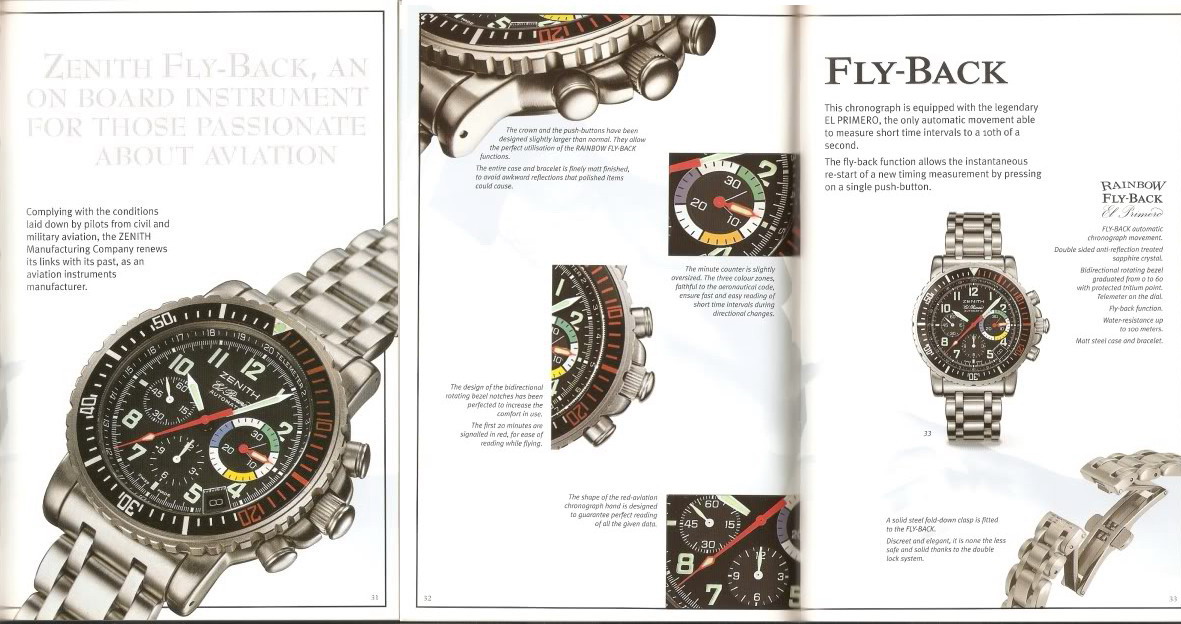

In 2000, Zenith introduced a flyback version of the El Primero movement, called the “caliber 405”, and this movement powered a series of chronographs called the “Rainbow Flybacks”.

More recently, Zenith has added the flyback feature to its “Striking 10th” El Primeros, creating the Stratos Flyback, as worn by Felix Baumgartner during his “Mission to the Edge of Space”. (It’s unclear exactly how the flyback feature might have been used on the freefall from 127,852 feet, but it never hurts to be over-equipped.)

TAG Heuer’s El Primeros

When LVMH (parent company of TAG Heuer) acquired Zenith in 1999, vintage Heuer enthusiasts were excited about the possibility of TAG Heuer using the El Primero movement in TAG Heuer’s classic or re-issue chronographs. However, in our preview of the Calibre 36 Carrera, we showed the nine TAG Heuer chronographs that have been powered by the El Primero movement, and noted that none of the nine is a classic / conventional / mainstream / normal chronograph. TAG Heuer has used the Calibre 36 movement in chronographs with innovative display systems, materials and construction, but as we review TAG Heuer’s portfolio of Calibre 36 chronographs, there is some disappointment that this legendary movement has never been used to power any of Heuer’s classic models.

Following as the TAG Heuer chronographs that have been powered by the Calibre 36 movement. We start with the Monaco 24 chronographs, and the Mercedes Benx SLR Calibre 36.

On the more conventional side are two Calibre 36 Monzas, one with three registers and one with two.

Two Grand Carreras have been pwoered by the Calibre 36 movement.

And last but not least, two Link Chronographs have used the Calibre 36 movement.

At Last — The El Primero Movement in the Classic Heuer

With the introduction of the Carrera Calibre 36 Flyback chronographs, TAG Heuer has answered the hopes of the enthusiasts who want to see the legendary Calibre 36 movement in a classic chronograph.

These new Carreras follow a conventional layout (meaning that they are not “bullheads”), with a traditional bi-compax design, and — as important as any feature, they have the “Carrera” name on the dial. Fourteen years after the El Primero movement joined the TAG Heuer family, we have the archetypal chronograph of the 1960s powered by one of the most brilliant movements of that same decade.

Flying and Driving

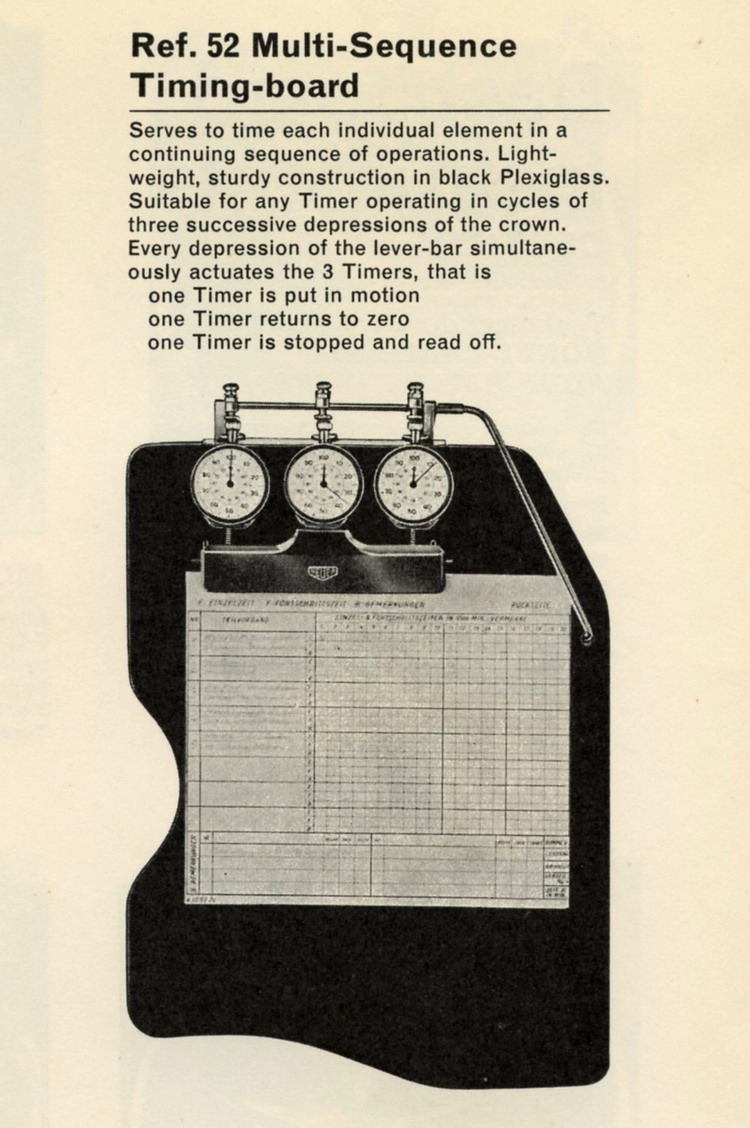

Pilots may be responsible for popularizing flyback chronographs, but the flyback feature also proves to be very useful for motorsports. In the 1960s, the standard piece of equipment for timing laps at the racetrack was Heuer’s Multi-Sequence Timing Board.

The lever running across the top of the board pushes the crowns of three stopwatches simultaneously, so that in an instant, one is stopped, another is started, and the third one is reset to zero. The person operating the stopwatches is able to record the time for each lap, taking the time from the timer that is stopped. There is always one stopwatch showing the time for the last lap, one timing the current lap and one sitting at zero, ready to time the next lap.

While a pit crew may have the luxury of using a Multi-Sequence Timing Board to time laps and record the times, the race driver will do better to time his laps with a flyback chronograph. Glancing at the running time at the start / finish line (or some other point on the track), and using the flyback to begin timing the next lap, the racer is able to time each of his laps. You can enjoy the same thrill on the interstate highways, pressing the flyback at each mile marker.

Beyond a Classic in a Classic

Had TAG Heuer simply offered a traditional-style Carrera powered by the Calibre 36 movement, the watch would have been well-received by chronograph enthusiasts. Who could have argued with the shape that has remained fresh since 1963, being powered by one of the legendary chronograph movements?

With the Carrera Calibre 36 Flyback chronograph, however, TAG Heuer has gone far beyond the simple “classic in a classic” approach. By incorporating the flyback feature, TAG Heuer evokes its rich heritage in pilots watches while also providing a feature that is useful on the racetrack. By using the stopwatch-inspired, double scale design, TAG Heuer reminds us of the forces that drove the design of the first Carrera — legibility and simplicity.

Everything Old is New Again

Skimming through the preceding 3,000 words and 50 images of this posting, one thing seems to be missing — the first 50 years of the Carrera. We have talked about the uses of flyback and split second timing, the re-design of Heuer’s dashboard timers and stopwatches, and several iterations of the El Primero movement. We have mentioned legendary watches from Longines, Hanhart, Breguet and Zenith (and some not-yet-legendary chronographs that have housed the Calibre 36 movement). But, you might ask, “what about the Carreras?” How can we present the newest Carrera, without the usual references to bauhaus design, the Mexican road race, the Rodriquez brothers and the sound of the word “Carrera”? What about the evolution of the Carrera and the hundreds of models produced by Heuer and TAG Heuer over the last 50 years?

The genius of the Carrera Calibre 36 Flyback chronograph is that we can introduce it without immersing ourselves in the 50 years of the previous Carreras. The new Carrera Calibre 36 Flyback draws on many elements that made the original Carrera the watch that it became. But even in the 51st year of the Carrera, we can say that this model offers new elements that we have not seen before in TAG Heuers classic chronographs — the flyback feature; the stopwatch-inspired style; and the legendary movement. This new Carrera Calibre 36 Flyback is not a continuation of the first five decades of the Carrera; instead, it takes defining elements that created the first Carrera, and uses these elements to create an entirely new Carrera, a perfect Carrera to lead TAG Heuer into the second half of the Carrera’s first century.

Jeff Stein

May 12, 2013